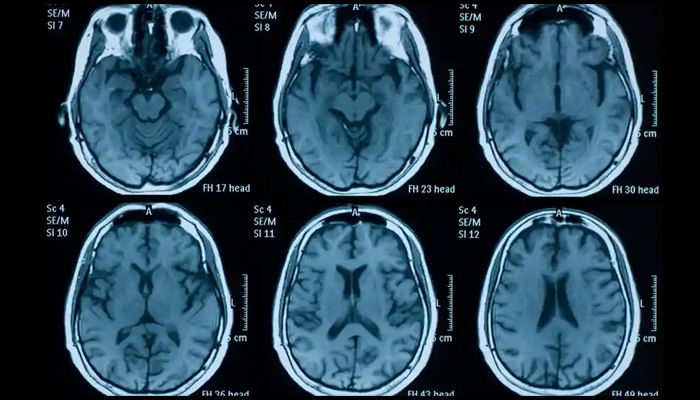

The primary significant research to analyze brain scans of individuals prior to and later when they get Covid has uncovered shrinkage and tissue harm in areas linked to smell and intellectual abilities months after subjects catch Covid.

It comes as the biggest research conducted to date of the Covid-19 genetics recognized 16 new variants related to serious illness, and named various existing medications that could be used to keep patients from getting seriously ill, some of which are now in clinical preliminaries.

In the brain research, scientists at the University of Oxford examined 785 individuals between the age of 51 to 81 who had their brain scans previously and during the pandemic as a component of the UK Biobank study. The greater part of them was Covid positive between the two scans.

And when these individuals were compared with 384 uninfected control subjects, the individuals who were positive for Covid had more noteworthy by and large shrinking of the brain and more grey matter shrinkage, especially in associated to smell.

For instance, the individuals who had Covid lost an extra 1.8% of the parahippocampal gyrus, a critical area for smell, and an extra 0.8% of the cerebellum, as compared to control subjects.

Disturbed signal handling in such regions might add to manifestations like smell loss.

The people who were covid positive additionally scored lower on a mental skills test than uninfected people. Lower scores were related to a more noteworthy loss of brain tissue in the areas of the cerebellum associated with mental capacity.

The impacts were more articulated in more aged individuals and those hospitalized by the illness, yet clear in others whose diseases were moderate or asymptomatic according to the study. Further scans are required to decide if these changes in the brain structure are super durable or somewhat reversible.

“The brain is plastic, which means that it can re-organise and heal itself to some extent, even in older people,” said Prof Gwenaëlle Douaud at the University of Oxford.

In independent studies likewise, researchers under the guidance of Dr Kenneth Baillie, consultant in critical care medicine at the University of Edinburgh, sequenced the genomes of 7,491 Covid patients in the ICUs in the UK. Analysts contrasted their DNA and that of 48,400 individuals who did not acquire the disease, in addition to the DNA of a further 1,630 individuals who experienced Covid moderately.

The research distinguished 16 new genetic variations related to admissions in ICU, incorporating genes responsible for blood thickening, the immune system and inflammation intensity.

It likewise affirmed the association of seven different genes that the group distinguished in former research, and which added to the RA drug baricitinib being tried on Covid patients. Information distributed last week showed that it diminished the risk of death from serious Covid by about a fifth, illustrating ” proof of principle that we can find new treatments using genetics”, Baillie said.

Among the new variations recognized is a little change in GM-CSF, a protein that assists with activating immune cells in the lungs after being infected. A medication focusing on this gene, otilimab, is being tried in individuals with Covid. “To have a genetic signal close to this gene gives us more confidence that this is a valid target,” said Baillie.

Others included variations in genes that control the levels of a focal part of blood coagulating – known as Factor VIII – which is upset in the most widely recognized sort of inherited bleeding haemophilia. Abnormal coagulating because of Covid could bring about diminished oxygen supply to basic organs, Baillie clarified.

“These results explain why some people develop life-threatening Covid-19, while others get no symptoms at all. But more importantly, this gives us a deep understanding of the process of disease and is a big step forward in finding more effective treatments,” he added.

“It is now true to say that we understand the mechanisms of Covid better than the other syndromes we treat in intensive care in normal times – sepsis, flu, and other forms of critical illness. Covid-19 is showing us the way to tackle those problems in the future.”